Outpost Freedom Trail

| Route 66 | Cities | Beaches |

|

Outpost Freedom Trail |

|

| Hiking The Freedom Trail is inspiring for an adult or a grade school kid. There is more American history to be learned in one day here than in any other single spot in the nation. We owe a huge gratitude to the people of Boston for appreciating these places enough to protect them from development. Even as skyscrapers rose around them, these 240 year old locations were lovingly protected that you might come here now and renew your understanding of who these people were and what they did. It is a pilgrimage everyone should experience. |  |

From the Shawmut, you access the Trail by walking down to the south end of Charlestown Bridge. It is clearly marked with signs, symnbols and brickwork embedded in the sidewalk. It begins by taking you East two blocks to Copps Hill Burial Ground. This was the oldest cemetery in early Boston, where the original settlers were buried. The graves shown here are those of Cotton and Increase Mather, early ministers who taught that America was God's own nation, a special people, with a special mission. |

|

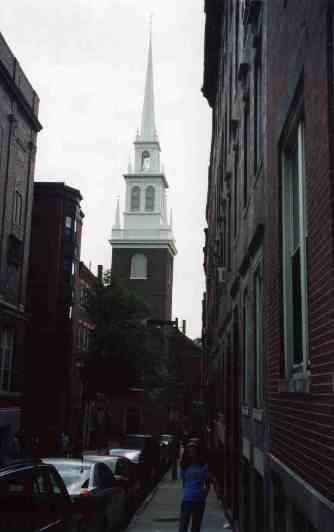

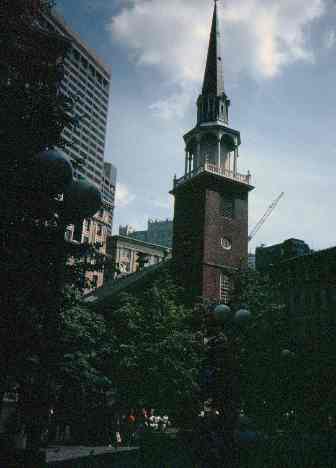

Only one block down from Copps Hill is The Old North Church, where first Increase and then Cotton preached. This neighborhood was the original residential section of Boston, with the business district down on the flat near the waterfront. By the time of the Revolution, it had already taken on an Italian flavor, and today is the greatest Little Italy in America. The church today looks exactly like it did in 1775 except for a few commemorative plaques. We are on the highest point on Boston and even with the skyscrapers, the church steeple can still be seen almost everywhere in the city. You should figure on at least half an hour inside, and another 15 minutes or so on the grounds and store. It is a beautiful church where services are still held, and everywhere you turn there are stories and anecdotes, like the organ stolen from a British ship carrying it to Montreal (below center), and Robert Newman (below left) escaping out the rear window with British soldiers pounding on the front door when they looked up and saw the lanterns. The plaza in the rear (right) is beautiful, a cool oasis on a hot Summer morning. As you hike further down to the Green Dragon, keep noticing the distance and terrain, remembering that Sam Ballard ("Johnny Tremain") had to outrace the British troops from the tavern up that hill to the rear plaza to let Robert Newman know how many lanterns to hang. Half of the men we honor today as Revolutionary War heroes were members here, while the others belonged to the newer and larger Old South Church. |  |

| Two blocks down the hill is Paul Revere's house. Still in good condition, it is open for tours. It was a fitting home for a prosperous silversmith, with a brick court yard and larger rooms than most homes back then had. Revere's father, Apollo Revoir, had come from France. Paul Revere is an Anglicized version of the father's name. Ironically, during his own lifetime, Revere was more famous as a gifted silversmith and metal crafter than as the midnight rider. His copper plating was used on the dome of the Massachusetts capitol building and |  |

the hull of the U.S. Constitution. Today, samples of his silversmithing are museum pieces and displayed by those families lucky enough to own them. One major silver set is on a buffet in the House of Seven Gables and several are shown off back in England. Revere became a Mason early in life, which is where he met the other prominent Bostonians who would become the Sons of Liberty. He saw the Boston Massacre and took part, dressed as an Indian, in the Boston Tea Party. He organized the surveillance of British |

|

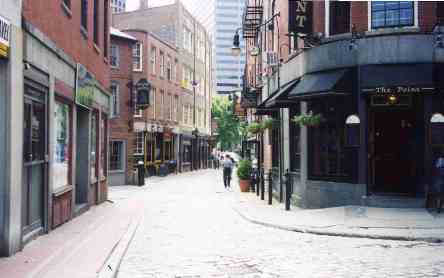

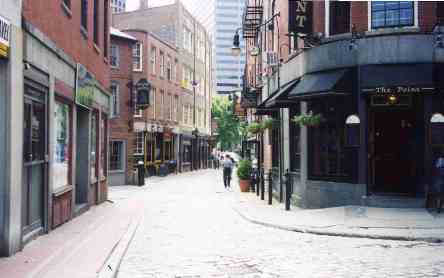

soldiers, using teenagers working in taverns, stables and stores as informants. As revolutionary fever increased, branches of The Sons of Liberty sprang up elsewhere, and Revere regularly rode to Boston, New York, and other cities to coordinate their activities. He developed a reputation as a fine horseman, which proved very helpful during the midnight ride. As you continue down Hanover Street from Revere's house, you might want to take a look down Salem St., a block over. British troops on Hanover forced Ballard to detour to avoid capture, so it was Salem (top right) he ran up. As you approach Union Street, notice Printers Alley angling off to the left. This was where the printers of Boston had their shops, where all the pamphlets and |

|

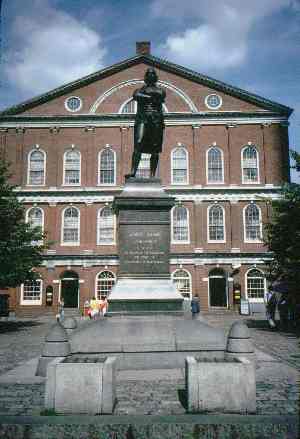

| posters were printed. They had to handset and hand ink the type (above right). The Green Dragon Tavern, with its gold and green outside decor, was a center of revolutionary activity. The British soldiers drank at the bar and met privately in a back room. The Sons of Liberty drank at the same bar and met upstairs. So both sides plotted their moves in the same building (see Green Dragon section under Restaurants). Right around the corner on Union Street is the Union Oyster House, the oldest restaurant in Boston and one of the best. Every body from George Washington to Daniel Webster to John F. Kennedy have eaten there, and the Kennedies have their own booth upstairs. One block further down Union Street is Fanueil Hall (right), with the statue of Sam Adams outside. This was the great Boston marketplace and still is, and this plaza has always been a hotbed of public protest about one cause or another. |

|

The rear of Fanueil backed up to the water then, and Crispus Attucks, a seven foot very muscular free black, was loading hogsheads (large kegs) while British troops were drilling up by the Statehouse (below right). Several small boys were pelting the troops with snowballs, then running down the alley to hide.The British wearied of this, chased the boys down, and began beating them. Attucks intervened. He flung the boys in the back of the wagon he was loading and slapped the horses to send them charging to safety. The British then turned on Attucks. He began retreating up the stairs, rolling down the loaded kegs onto the soldiers. Those kegs weighed a ton and took out many of the infantry but someone finally shot and killed Attucks. A crowd had begun to gather, and as Attucks fell they charged. The British opened fire, and the Boston Massacre began. The round marker embedded in the sidewalk (below left) marks the Boston Massacre, which turned the |

|

general public against the British. The Statehouse (right) requires a visit. This was the governmental headquarters for the century leading up to the Revolution. It is still a beautiful building, and the Freedom Trail Headquarters. The National Park Visitor Center is across the street in that partially hidden grey building. It's a pretty good place to pick up maps, brochures, postcards, film, books and souvenirs. They can answer most questions. There are rest rooms. Grade School and Middle School kids can pick up the packets to work on their Junior Ranger badges, and there are materials relevant to Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts. Historians conduct tours on schedule but on this day you need to keep moving. |  |

| At this point we recommend a slight rearrangement of the usual Freedom Trail route. We suggest as you leave the Statehouse, you go up Court Street, then turn left on Tremont. One block will bring you to the Old Granary Burial Ground, where most of the Revolutionary heroes lay. To the right here is Paul Revere. Below left is John Hancock and below right is John Adams. As you walk around the rows you will come to Crispus Attucks, the Boston Massacre victims, the Laphams, Dr. Warren, James Otis, and pretty well the entire list. It is amazing to notice how every day both adults and children leave notes, cards, pictures, money and small flags at these graves. Every day the caretakers remove the items and next day more arrive. They are especially prevalent on Memorial Day, Christmas and their birthdays, and become a landslide on July Fourth. It has been 240 years and still people come. |  |

And they come from everywhere. While we were there, just one June day , buses unloaded from Texas, Oregon, Maine and Missouri. A Golden Age tour, a senior class, a tourist group from Japan, a church group. They stand in line to have their pictures taken at each stone, place their offerings, stand with hands clasped in front of them for a silent moment, then move on. We had to hang around for 45 minutes for the chance to get these photos unobstructed. The caretaker told us it goes on year round. People come with umbrellas in April, bundled up in parkas in January, guzzling icewater in July. This seems especially interesting since our schools no longer spend much time teaching Early American History. the media totally ignore it, Hollywood doesn't make any movies about it, and patriotism is out of fashion. But somehow people are still aware of who these men are and what they did, and they come to honor that. |

|

It is interesting to note that although Crispus Attucks was the only black killed in the Boston Massacre, there was not one moment's hesitation to bury him here in an upper class and all white cemetery. Attucks became the first hero of the Revolution and his name is on everything from streets to schools to parks. Dr. Warren's death at Bunker Hill was the greatest loss of the Revolution. Most people saw him as the brains behind the Sons of Liberty and his loss cost America much needed leadership. After we won independence, a decade went by during which serious errors were made. If Warren had survived, he might have become one of our early presidents, but even if not, his guidance could have averted some of the young nation's worst mistakes. |

|

From The Old Granary, cross the street to the Kings Chapel graveyard and find the triangular granite shaft marking two graves with a scripted A. This marks the remains of Anne Christian, the woman we know as Hester Prynne in Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter. Then pass the Chapel and head down School Street one block to the Old South Meeting House. This was the second major church built in Boston as the city expanded Southward. The Sons of Liberty who did not attend Old North were members here, and some of the meetings and rallies were here because it was larger. One of those was the December meeting about the tea controversy. Most members of Parliament had invested heavily in the East India Tea Company. Since 1620 it had been one of the most profitable English businesses but since 1770 mismanagement had plunged it into debt and threatened bankruptcy. Rival companies were now outmarketing East India, and stale tea was backing up unsold in its warehouses. To bail out the company and their investments, Parliament established a monopoly. Only East India tea could be sold in The New England. |

|

Not only that, but Parliament imposed a tax on that tea, a tax collected in America but not in England. The monopoly guaranteed East India a market for its tea, and the tax would be returned to the company to help pay down its debts. Americans, at that time being 90% English, were tea drinkers. They understood and appreciated fine tea. They objected to Parliament's actions for several reasons. The Puritans first, and now others, were bringing new and exciting flavors back from Oriental and other sources. Americans wanted the right to buy those flavors. Second, East India, taking advantage of its monopoly, was charging higher prices. People wanted the right to buy less expensive teas. But the worst issue was that, having a monopoly, East India was unloading its stale tea on America so it did not have to dump it, arrogantly thinking the ignorant Colonials would not know the difference. Americans had responded to this arrogance by boycotting tea. The unthinkable, drinking coffee, had become an act of patriotism. East India tea was rotting in the harbor. Americans wanted it sent back to England. |

|

So the Sons of Liberty had sent a petition to the Governor demanding (l) repeal of the monopoly, (2) repeal of the tax, and (3) return of the tea. But Dr. Warren thought it unlikely Parliament would budge. So he had a hundred supporters ready outside, dressed as Mohawks to avoid punishment. He had Rab Sills stationed at the first balcony window in the picture at left. The code phrase would be "This meeting can do nothing further to save the country." Sure enough, the messenger returned from the Statehouse with a decisive "No." |  |

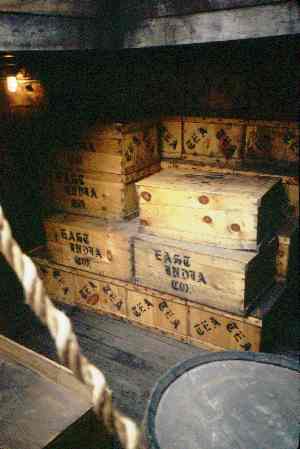

| Adams interrupted the discussion from the podium at left, above, announced the reply, then uttered the code phrase. Sills opened the window and whistled to the crowd on the street. As they headed the five blocks to the harbor, he and several men from inside quickly changed clothes, put on facepaint and hurried to catch up. The Boston Tea Party had begun. The tea was in the hold of The Beaver, a small cargo vessel. Dumping it in the harbor was symbolic enough, but the Sons of Liberty then marched through town to their Liberty Tree in a sort of 1775 pep rally. |  |

Today, The Beaver still sits in the harbor with its hold full of East India tea(below left). Once an hour, you can board the ship, enter the hold (above right), haul a bag up, and dump it overboard. A host in period dress (left) goes over the facts with you, answers questions, and supervises the dumping of tea. You can even buy a small bag, box or tin of East India tea (it's still a major British company) or a model of the ship to take home with you. The ship underwent a major restoration in 2005-6 so is in excellent condition, and there's a new visitor center. |

|

From the waterfront, take Summer Street, which becomes Winter Street, back up the hill to Boston Common. Walk on across the Common to the New Statehouse (new in the sense that it replaced the Old Statehouse so America would not be using a British landmark). Paul Revere and Sam Adams laid the cornerstone in 1795. The building was completed in 1798 on property John Hancock gave right next to his own hilltop estate. In 1802 Revere and his son covered the dome with copper plating. The gold leaf was added in 1874. The statues on the yard are of the heroes of Massachusetts history, with the most recent being John F. Kennedy. |  |

| From The Statehouse, you should meander across the Boston Common, one of America's most beautiful city parks. An oasis of lakes and huge trees surrounded by skyscrapers and historical shrines, the Commons has played its own role in history for four centuries. You can rent a boat and circle the lake, feed the ducks, or lay on the grass and rest your feet. It was the pasture for Boston's livestock, then a drilling ground for both British and Colonial troops. "The Tragedy of the Common" made it a sociopolitical metaphor. |  |

When you reach the far border of The Commons, follow Arlington Avenue to your right. At the corner of The Commons, at the base of Hampshire House, you'll find what was the Bull & Finch Pub. It was an award winning neighborhood bar and inspired the tv series Cheers. So many visitors came looking for the bar named Cheers that in 1990 owners abandoned the Bull & Finch name. There is also a Faneuil Hall Cheers location, but it was the Hampshire House bar you saw on tv. |

|

From Cheers, follow Beacon Street along the edge of The Commons to Charles Street. This is the business street of Beacon Hill, Boston's most elite district. The nation's most famous antique shops are along this street. Take it to the left, down the hill past the Charles Street Meeting House, to Pinckney Street. Turn right. You will now walk through Louisburg Square (right). This is Boston's avenue of fame, where a long line of famous authors, politicians, writers and businessmen have lived. Take Joy Street down to Cambridge Street and the Old West Church, take Staniford Street over to Causeway, and you'll be back at The Shawmut Inn. You might have time for a break before heading to The Union Oyster House for dinner. |  |

|

|||

|