Martins Fork

| Route 66 | Cities | Beaches |

|

Martins Fork |

|

| Auxier Ridge | Martins Fork | Grays Arch | Rush Creek | Pinchemtight | KoomerRidge | ChimneyTopCreek | ParchedCornCreek | SwiftCampCreek |

| IndianStaircase | Castle Arch | Osborne Bend | Raven Rock | Red Byrd Arch | Indian Creek | Revenuers Ridge | Copperas Falls |

Martins Fork is the hike we begin every season with. For our new members who have never been hiking before, it is a wonderful introduction. But it is also full of variety, a conditioning walk without being exhausting, and very photogenic. To reach the trailhead, leave the Mountain Parkway at the Slade exit, turn left, go under the parkway, turn left on 11-15, and drive to the Nada Bridge. Turn right on 77, drive through the little village of Nada, climb the hill, go through the tunnel (photo right), follow the twisting switchbacks down the hill, and at the bottom immediately to your left find the parking lot. The tunnel (photo right) is the old railroad tunnel the logging trains used to haul out the timber from 1880-1920. Nada Tunnel is like a magic entry to a different world. On one side is the strip village of Nada, originally the home of workers for the Dana Timber Company. On the other is the deep forest that is today's Gorge. During those 40 years the Gorge was completely denuded of trees. So what you're seeing today is a 100 year old forest. To find the trail, cross the road, turn right, and hike along it until you come to the sign and wooden bridge. Especially if you have new or infrequent hikers along, allow about four hours. Bring the usual day pack containing snacks, lunch, two bottles of water, rain gear, change of socks, foot powder, camera, and binoculars. Somebody in the group should have a first aid kit. We highly recommend wearing two pair of socks, one thick, one thin, and thoroughly dusting the feet, the outer side of the thin socks, and the outer side of the thick socks, before lacing up the boots. We also urge a few minutes of stretching exercises and a good pair of trekking poles. This is not a long hike, but after a Winter of inactivity it offers a strenuous workout climbing and then descending Rhododendron Hill. Many hikers consider the descent more strenuous than the climb. |

|

|

As soon as you cross the wooden bridge, a sign points right to The Military Wall. This is prime rock climbing country. The Wall is only 0.8 mile off the main route, so you might wish to follow it and watch for a while. The Military Wall Trail climbs the shoulder and passes Slot Rock (photo, left), You may wish to pause to walk through, behind and possibly atop this unusual little formation. The large boulder apparently cracked as it tumbled down he slope. Past it the trail begins climbing steeply over rocks and gnarled tree roots. This is really a beautiful trail, through a lush forest with large boulders laying on both sides. You have views both up toward Tunnel Ridge and down toward Martin's Fork. Back in the 20th Century this trail did not exist. The climbing community built it once they discovered the Military Wall, and they maintain it. On weekends this is extremely busy. Even on weekdays, there are people practicing their climbing skills. |

| As you approach the Wall, high on your right is a gigantic rock shelter. You'll notice signs and wire warning you to keep away. This is one of many ongoing archaeological digs in the Gorge. This shelter was used by the Adena and many artifacts have been recovered here. It's tempting to disregard the signs and snoop around, but please resist the temptation. The actual Wall begins just around the corner and you'll have plenty to occupy your attention. |  |

|

The scene at the Wall is usually busy. Some climbers are on the sandy floor, tethered to ropes. They're "belaying," meaning serving as counterweights to partners high on the rockface. If the climber were to slip, he couldn't fall far because of that counterweight. There are small anchors inserted in cracks in the rock faces. They were placed there by expert climbers for the use of all the other climbers. Climbers can thus attach their ropes to these anchors as they climb, so while they may appear to be in high risk situations, in fact they're protected from falling. They may slip, and if you stand there long enough you'll see some do so, but they won't fall. There are various "routes" to the top, some relatively easy and some more difficult. |

Climbers you see in the Gorge are not beginners. They've already worked back home on their skills, using artificial climbing walls and real rock faces with easy routes By the time they come to the Gorge they're ready for challenges. Climbers from Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois come here every weekend. Those from further away, including western states and many foreign countries, try to make it hre once or twice a year. Back on the main trail you'll find yourself in a 3/4 mile long, narrow, wooded valley between towering cliffs (photos top and below left). The stream, Martins Fork, is usually small and meandering. When it is, this is a fairly dry trail which crosses back and forth by way of bridges. But if you try this trail in the Spring or after several days of rain, it may be very muddy. Like all of the Red River Gorge, Martins Fork is best hiked in the Spring or Fall. It gets extremely hot and humid in June, July, August and early September. You can get some spectacular photos here in October when the sunlight is streaming down through bright red, orange and yellow leaves. |

|

|

You'll have a pleasant stroll along Martins Fork hardwoods, pines, ferns and, in season, wildflowers. Small fish called darters live in this stream. So do crayfish. If you look carefully across the stream from the trail you can find raccoon, possum, skunk, and wildcat tracks in the sand and mud. Perhaps becaue it was always in such deep shade, the Adena called this The Valley of The Poor Hunting. They rarely came here, and neither did their successors the Shawnee. Since no one else ever came here, Daniel Boone established his headquarters back under a cliff at the head of the valley during his first year in Kentucky. If you're a Fern lover, this is Paradise. This is one of the greatest stands of Ebony Spleenwort (below) in North America. It is also home to great colonies of New York Fern, Bracken Fern and Maidenhair Fern. They're not quite as plentiful but you can find Cinnamon Fern, Grape Fern and Walking Fern along the main valley and, in the upper valley, Horsetail, which is a cousin to the ferns. |

Ferns reproduce by spores produced on the undersides of their leaves. In Spring you can see the light brown spores creating a ridge in the center of each leaf. It's tempting, but remember it's absolutely illegal to dig any of these ferns and try to take them home with you. They wouldn't survive anyway. You can't duplicate the unique mix of soil moisture, humidity, acidic soil, deep shade, and surrounding fern plants. If you want a home fern garden, you're better off buying from a fern supplier, who sells specially bred ferns that thrive in home or garden environments. At times, especially in the Spring when the valley is dripping wet and humid, you can find a dozen species of Fungi here, but other times, especially in August and September, when the valley is dry, you may not see a single one. Martins Fork is also home to 10 species of Moss. Most people take Moss for granted and pay no attention to it. But research has found that mosses soak up, hold and slowly release a huge percentage of the water moving through an ecosystem. |

|

|

Martins Fork is home to several species of Salamanders. The most spectacular is the yellow and black Spotted Salamander. You're most likely to see these in April and May, when they're seeking mates. The rest of the year, they stay under leaves, logs, rocks and dirt. Look for them on large moss carpets. In Kentucky Spotted Salamanders hibernate November to March. Like all Salamanders, Spotteds have the gift of regeneration. If a predator bites off a tail or leg the Salamander grows a new one. You may see one with a partial tail or leg while it regenerates. Spotteds also have poison glands on the neck and back. If grabbed by a predator, they secrete a toxic milky liquid that causes the snake, fish or bird to drop it quickly. If you pick up a Spotted and it releases a puddle of this liquid, wash your hands immediately. Spotted live an amazing 32 years. They eat centipedes, millipedes, slugs, insects, worms and spiders. A Salamander is incredibly quick, fast and agile. Females lay eggs in jellylike balls in the water. |

The trail mostly follows the stream, but at one point it climbs the west bank and winds along for a hundred yards looking far down on it. Eventually it descends and again follows the stream. The small fish you're seeing are not juveniles. These are Darters, a family of fish which have evolved downward in size to allow them to populate these streams too shallow for larger fish. Adult Darters are beautiful with their bright colors and varied designs. They look like their tropical cousins. Darters are extremely sensitive to pollution, so their presence here indicates that Martins Fork runs clear and pollution free. (However, it contains Giardia Lamblia, so you have to filter it.) Keep in mind that the Martins Fork valley was logged between 1880-1920. Photographs show not one tree standing in 1920 when the loggers pulled out and took up the railroad tracks. So this forest you're seeing is only 100 years old. |

|

|

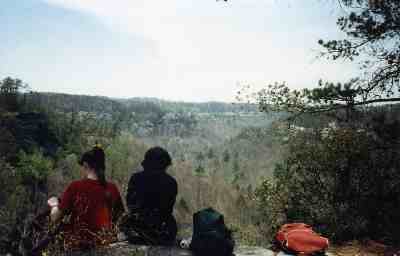

After 3/4 of a mile you come to a fork. You want the trail to the left (it's a loop; we'll eventually come back down the one to the right). You suddenly begin climbing and leave the stream behind. You will switchback 400 feet in half a mile. This is a very challenging climb for new or out of shape hikers. You're scrambling over roots, rocks and sometimes downed trees that were felled by Winter storms and haven't been cleared yet by trail crews. For 50 years or so this was the greatest Rhododendron Forest in North America. They grew to tree height and shaded out everything else. The trail literally came up through Rhododendron tunnels. But several severe storms and a major fire in the 1980s and 1990s devastated the upper valley and destroyed the Rhododendrons. What you see now is a young forest that has grown back in the last 30 years. It's an impressive forest, but with the Rhododendrons cleared out and sunlight penetrating to the forest floor, other trees were able to come in. There are plenty of Rhododendron still here, and many of them have again grown to impressive sizes. But they no longer dominate the landscape. Halfway up the climb, you'll see a rock outcropping to your right. This is a great rest stop after the long hike through the valley and a difficult climb. It provides fine views of the forest (photo, left) and a broad rock surface to relax on. You'll see reddish brown ridges on that rock surface. Those are iron ore. In the 1800s, in this four county area, men constructed iron furnaces and tried to create an iron industry. But the iron ore wasn't concentrated enough, and the local furnaces couldn't compete with those in other areas of the country with much greater concentrations. The remains of those old iron furnaces can still be found and some are now historical sites.

|

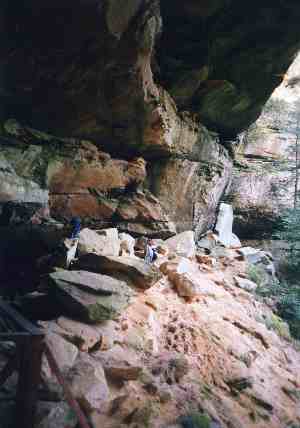

Past this rest stop, you'll struggle on over more roots, rocks and downed trees. Finally, you'll cut back to your left. The photo at right shows three hikers (bottom) making their way along the cliff. You'll find yourself facing a large rock expanse heading upward. For decades there was a staircase here, but the forest fire took it out. Now there are stairs etched into the rock. Without too much effort you can pull yourself up. In the process you should notice the combination of sandstone and limestone that you're climbing. These deposits were laid down forever ago when this part of North America was floating down at the equator and under shallow ocean water. Since then, obviously, the continent has drifted northward and the ocean has receded as all its water was drawn up into icecaps at the north and south poles. You may also find yourself eye to eye with a Fence Lizard or Skink. The Fence Lizards are Kentucky's version of the Texas Horned Toad. They have rough, scaly ridges and can run very fast across these rock faces. Their coloring will adjust to match their surroundings. The ones living in the forest take on a dark hue. These rock face inhabitants take on a lighter hue. They live on insects and other invertebrates. They can climb trees or cliffs. Fence Lizards live about seven years in captivity and about five years in the wild. The Five Lined Skink is common in the Gorge. (Four other types are found elsewhere in Kentucky.) They spend most of their time over in the leaves and underbrush, but venture out onto the rock faces to bask in the Sun. Like the Fence Lizard, they eat insects and other invertebrates. If you pick one up, it will try to bite you, but it has bony ridges instead of teeth and can't puncture your skin. |

|

|

Precisely as you reach the ridgetop, look for a faint trail leading off to your left. If you start hiking on level ground you've missed it. Go back and look again. This is the well disguised entrance to Harrison Point, one of the great lookout points in the Gorge. Harrison Point is a fine lunch stop and a great place for photographs. You're looking all the way back down Martins Fork, framed by snaking cliff faces to the right and left. Red Tailed Hawks can often be seen riding the thermal currents, and in late evening ornithologists come here to record whippoorwill calls. Since this location is so scenic and so close to the road, it receives frequent use as a campsite. You may find fire scars not cleaned up by recent campers. We always carry trash bags and clean up such blemishes, and you could do everyone a favor by doing the same. |

| If you spend a nice long lunch at Harrison Point, you're almost certain to meet several of its inhabitants. First among these is the Vole. Voles are cousins to Lemmings and Hamsters. They're sometimes called Field Mice or Wood Mice but that's incorrect, since they're not related to Mice. Voles live on fruits, nuts, and leaves of annuals like Grass. Voles living on Harrison Point have also developed a fondness for the blackberries which grow here and food particles left by hikers and campers. They're great burrowers and all of Harrison Point is underlain by their tunnel system. In captivity a Vole can live three years but in the wild they're usually picked off by Owls, Red Tailed Hawks, Snakes and Foxes. Voles are famous for their sexual fidelity; males and females bond for life. A Vole community, such as the one at Harrison Point, shows a high degree of social organization. Voles will comfort each other, defend each other, assist each other, and mourn the loss of community members. They show a high degree of intelligence and curiosity. Don't be surprised if a Vole shows up to observe you while you eat lunch. They seem not to be afraid of humans, although the shadow of a hawk passing over the rocks sends them diving for cover. Don't set food down unguarded; they're quick and will snatch it. |  |

|

When you return to the trail, turn left and proceed to the intersection, then turn right. A short walk will bring you to the Greys Arch Parking Lot, with portajohns, picnic tables and drinkable water. After refilling your water bottles and stopping at the porta johns, follow the parking drive around to your right and the trail marked D. Boon Hut. Follow that and find yourself again dropping into the valley. If it's Spring, you'll be greeted by one of the nation's great displays of Pink and White Lady Slippers. They literally carpet the whole hillside. You'll descend a long series of staircases (photo, left), then turn left and follow the base of the sandstone cliffline (below). If you're here in April or May you'll probably still see ice. The deep overhangs hold in the cool temperatures and ice here hangs on til June. |

The trail here runs fairly level but it's tricky as you work your way around and sometimes over boulders and large rocks. On a hot, humid day you'll love the cool air. Regulations do not permit camping back under these giant overhangs. And then you come to one of the great historical locations in Kentucky : the remains of the handmade hut where Daniel Boone spent his first winter in the state. He chose the site well. Deep back within an overhang, the hut was never rained or snowed on, which is why it's lasted this long. He could build a fire and cook or warm himself without getting out in the weather. He could look down the long valley and, with the leaves off the trees, see anyone coming up toward him. The ridge above is too high and steep for anyone to come over the top; they had to come around and approach him from the front, in full view. Shielded from the wind in cold weather, a natural spring kept the rock shelter cool in hot weather. Daniel had a supply of fresh water without exposing himself to an enemy or going out in harsh weather. A chain link fence (photo, below) prevents anyone from tampering with the remains of the hut. You can walk along the fence and get good views. The hut has been radiocarbon dated by Yale University researchers and other tests have been run by University of Kentucky professors to verify that, yes, this was the hut built by Boone. This is a huge rock shelter, and further over, there's another set of remains here, those left by Saltpeter processing. Saltpeter (potassium nitrate) was and still is used in black gunpowder, explosives and fireworks. Historians have determined that Boone learned how to extract Saltpeter from the deposits in caves and rock shelters and make his own black gunpowder. Modern gunpowder is white and does not produce the smoke that the old rifles did. Black gunpowder has to be kept absolutely dry, which is why frontiersmen such as Boone carried powderhorns made from animal horns. During the 1800s, pioneers returned to this and other rock shelters in the Gorge to mine and process Saltpeter, and some of their equipment has also been left here. But it is separate from Boone'e artifacts. |

|

|

He could stock a whole winter's wood back in the dry recesses, and the heat from a fire would be reflected by the rock walls. It is unlikely he actually slept in the small hut very often, since sleeping between the fire and the wall would have kept him quite warm and dry and allowed him to keep a watchful eye on the trail approaching from below. Yale University has carbon dated the hut and validated several artifacts, so there isn't much doubt this really was Daniel's home away from home. A chainlink fence safeguards the hut, the site, and a nitre site further along the ledge. |

From here on, the trail cuts wide around the cirque, then gradually descends through beautiful forest The photo to the right here, taken from the Boon Hut, shows a group of hikers having already descended to the valley below. You can see the trail in the lower left of the photo. The trees up here, at the head of the valley, are mostly Beech and Birch with a scattering of Rhododendron. This photo is taken in early Spring so the Rhododendron, always green, stands out against the dry leaves. The other trees have not yet leafed out. Once you return to the creek, look for an extensive colony of Ground Fern, Horsetail and Liverwort, three primitive plants rare everywhere else but common here. Then you're back on the Martin's Fork Trail, where you began several hours ago. It will take about 30 minuites to get back to the parking lot. |

|

|

|||

|